Piecework: Related Material

Return to Sender (after Mary Jane Smith and Mary Morrell Smith, 1861-65)

Afterthought (after Anonymous, 1880-1890)

Correspondence (after Rachel Blair Greene, 1885-1895)

Sender Reverse

Antecedents

Introduction

Unlike many previous projects in which I devised strategies for discovery while avoiding as much decision-making as possible, Piecework was originally conceived as a looser project in which I could return to my roots as a visual artist, making decisions about color and form. Unlike earlier projects there would be no single set of rules limiting my approach and no one piece would have to look very much like another. As you will see below, I would eventually find myself drawn to new kinds of strictures that led in unexpected directions within Piecework and on to future projects.

Most of the pieces from the project are based on common quilt-making patterns including Tumbling Blocks, Grandmother’s Flower Garden, and Double Wedding Ring. Some works refer to less well known quilt making practices. The handwritten names and addresses in Postscript, for example, reference the tradition of Signature Quilts in which, for a variety of reasons, each block of a quilt would be inked or embroidered with a different person’s signature.

Detail of Postscript, 2009

Quilt, Tumbling Blocks with Signatures pattern, Adeline Harris Sears, begun 1856, Collection of The Metroplitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

I have also made references to Japanese mending traditions that reflect that culture’s veneration of saving and re-using treasured objects which have been damaged but not destroyed. Fitting together the large sections of Grandfather’s Garden revealed unexpected gaps in a few places and rather than render them invisible I echoed the method known as kintsugi in which broken ceramics are repaired with a lustrous gold lacquer to memorialize an object’s history. The gaps in Grandfather's Garden are filled with bright orange pieces of parking-ticket envelopes. In Afterthought the blue background refers to boro textiles. Boro is a denim patchwork tradition involving repurposing worn fabric from work clothes to make new things, from kimonos to futon coverings.

Detail of Grandfather's Garden, 2013

Tea bowl, Satsuma ware, White Satsuma type, Kagoshima prefecture, Japan, 17th century, Edo period, Collection of the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Halfway into Piecework, and having fallen into a kind of obsession with several 19th-century American quilts, I found a new way of working. You can think of a traditional quilt maker as a performer, creating a new iteration of a chosen pattern each time they approach it. Working outside of the tradition I saw that I could go a step further and perform an existing quilt as if it were a musical score, approaching the original as a set of instructions dictating a strangely precise yet new and alternate version of itself. Without access to the exact materials of the original and by using what had become an extensive collection of security envelope patterns my performance would, of necessity, become something else. Furthermore, I would base each attempt only on the actual catalog reproductions I had access to, the internet being so much less helpful at that time.

I took a strange joy in knowing that because I could never match the original, a kind of failure was built into my process before I started. I sometimes think of the children’s game Telephone where one person tells something to a second who must try to remember and recount the whole thing to a third and so on with mistakes cropping up quickly, the point being that Da Vinci might come back around the circle to you as Potato. The effort of telling is more interesting than accuracy, and the mistakes may be more true.

I did not realize how fruitful this way of working would be as Return To Sender led to Afterthought and then Correspondence. Much later I decided to make a piece called Sender Reverse which, instead of being based on a 19th-century quilt, is based on the back side of Return To Sender. Correspondence would point the way toward several new projects all grouped under the title Forwarding and based on collaborating with Rachel Blair Greene’s 19th-century original in a different way.

I am often drawn to using the most basic and functional graphic design as source material. In the past I’ve used the lines and boxes that define newspaper stories and the typography of classified ads. I’ve worked with mail-order catalogs, advertising circulars, and business documents.

When I first began looking at the different security patterns I found in the daily mail I was curious but only a little, saving some randomly in a box in my studio. Only after working with embroidered domestic textiles and then becoming fascinated with American patchwork quilts did I one day open that box and make the connection between the patterns printed on the envelopes and the patterns printed on the fabric scraps in quilts. I could see right away that, in each direction, one would make it possible to make work from the other.

As I gathered together an archive of materials and sources I made some other discoveries. Of course the most basic patterns pop up in both places — stripes, dots, hexagons, etc. but many security patterns actually mimic the look of woven fabric itself. A few even utilize geometric patterns that resemble quilt-making patterns. I’ve found security patterns that match Tumbling Blocks, resemble Double Wedding Ring, and even a security pattern that looks just like a Crazy Quilt.

Security Pattern Archive, clockwise from left: Black 93, Blue 2, Blue 91, Black 4 (var.10)

Security Pattern Archive, clockwise from left: Blue 199, Black 100 (var. 2), Black 100, Blue 41 (var. 2)

During the course of this project and to a lesser degree in the years since, my studio index of security patterns has grown to include just under five hundred entries. Most are blue or black with a fair number of green, purple and a handful of other colors. Some patterns are generic and occur in a surprising variety of minor variations and across colors. But many patterns are proprietary to corporations, both with and without logos and trademarks. I have tried to exploit the variety of the archive as a whole and also sets of the minor variations found within particular patterns.

Index of Security Envelope Pattern Archive

The vast majority of patterns seen in the project come from companies based in the United States and a number are European. I have always wished I had more patterns from other cultures and parts of the world. For better or worse I no longer come across as many patterns in my daily life, as cost cutting and the age of the internet reduce our reliance on and the formality of paper transactions.

I am grateful to the many people who saved and sent me empty envelopes but most of what I collected came through my own front door. Between 2006 and 2013 I saved everything I could: personal mail, junk mail, invoices and insurance statements, express deliveries, etc. During those years I learned that if you waited long enough your household mail would provide the bullet points for the story of your life. It seemed like everything was present in some form of mailed content. Friends and family, finances, education, health, work, death, birth. Letters, W-2s, alumni requests, denials of coverage, sales statements, wedding invitations. Much had to be inferred but my archive of envelopes began to feel like an autobiography — and that resulted in several pieces which documented my past including Postscript and Missive.

Another thing I came to understand over the course of my engagement with the protective outer coverings of the daily mail is that it would all change. During the ten-year period that Piecework was in process email succeeded in taking over almost every aspect of formal communication. Letters ceased. Many companies even stopped using their proprietary patterns for billing and communications, saving half a cent by sending out each invoice in a plain white wrapper. Maybe they were subtly encouraging a societal shift toward online bill-paying systems. My project began to take on a documentary aspect that I had never foreseen. I made the piece Double Archive With Rotation to contain two copies of every pattern I had at the time it was made, but had to break the border to add two more rows of additional material. The first set of patterns is mirrored along a horizon line and offset by 33%. Grandfather’s Garden uses almost as large a variety of patterns in its hexagonal rosettes.

Works from the Piecework project are put together using quarter inch tabs much like a quilt would have seams. Whereas fabric seams would be folded back flat and hidden to one side or another, the glued paper tabs here project back behind the surfaces and result in a semi-rigid structure in low relief that reads more as an object than as a flat surface.

Detail of verso of Sender Reverse, 2018

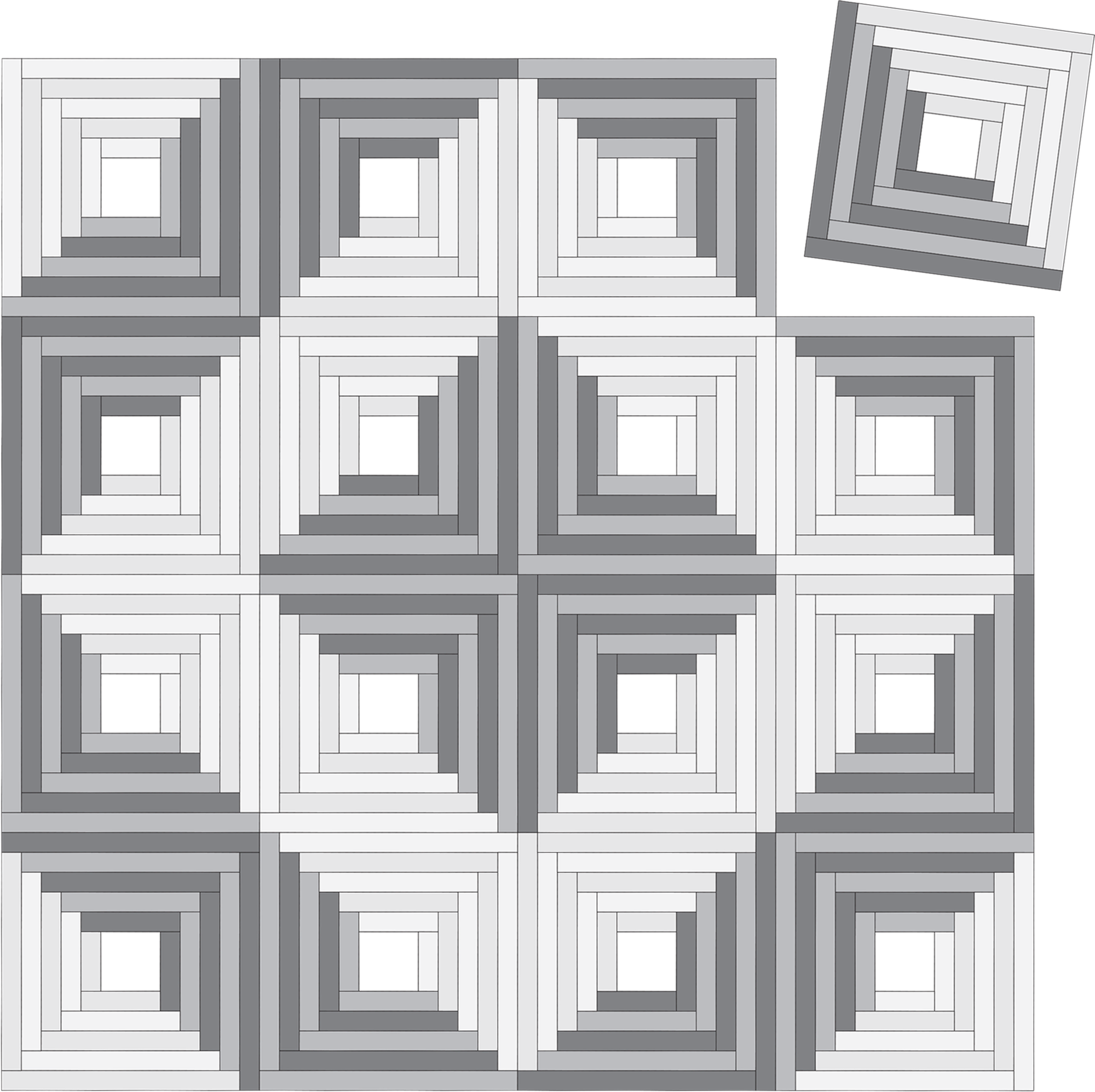

Return to Sender (after Mary Jane Smith and Mary Morrell Smith, 1861-65), 2010

Left: Return to Sender (after Mary Jane Smith and Mary Morrell Smith, 1861-65), 2010 Right: Mary Jane Smith (1833–1869) and Mary Morrell Smith (1798-1869) Log Cabin Quilt, Barn Raising Variation, 1861–1865, Collection of The American Folk Art Museum, New York, New York

Mary Jane Smith’s Log Cabin Quilt, Barn Raising Variation has always exerted a strong pull on me. I’m interested when an artwork seems to be in conflict with the intentions of its maker — and this piece confounds me.

Log Cabin quilts are pieced in blocks composed of narrow strips of fabric which ring a central square. The fabrics, separated into lighter and darker groups, divide each block diagonally into two triangles. The resulting blocks can be combined with one another in a surprising variety of ways.

Log Cabin, Barn Raising Variation Diagram

Barn Raising Variation quilts have blocks arranged as nested diamonds with the smallest diamond surrounded by alternating light and dark bands. The arrangement of the whole is a larger iteration of the block pattern itself, just turned and resting on a corner instead of a side.

The first unusual thing to notice about Mary Jane Smith’s quilt is that the nested diamonds are centered vertically as is usual but not horizontally. There are 12 rows but only 11 columns. As a result the middle of the pattern is offset, not one block but half a block to the left. This unstable arrangement means that the left edge of the quilt has a dark point touching its middle and two dark corners, while the right edge has a light point touching the middle and light corners. It’s a simple but unusual feature that gives the piece a lot of movement and it would be easy to stop there but something else is going on that is less obvious.

Taking a closer look it becomes clear that the central diamond, composed of four dark triangles, is internally symmetrical on its diagonal axes down to the last detail, i.e., the same fabric is used in the same order for the opposing pairs of blocks.

Detail of four center blocks from Mary Jane Smith (1833–1869) and Mary Morrell Smith (1798-1869) Log Cabin Quilt, Barn Raising Variation, 1861–1865

Detail of four center blocks from Return to Sender (after Mary Jane Smith and Mary Morrell Smith, 1861-65), 2010

This precision is maintained through the first surrounding pale diamond and into the next larger dark one. But at the outer extents of this third band, where the lower left and upper right parts of the outer points should be matching, the symmetry disappears.

This might make sense if Smith had begun in the center of the quilt and grew tired, abandoning the effort altogether, but this is not the case. Further out from the center the quilt includes moments of symmetry (which must be intentional) as well as moments without. Why would someone go to such extremes of precision, matching hundreds of inch wide strips of colored and printed fabric while placing others randomly?

I couldn’t make sense of it and decided that the best and only way to truly understand would be to analyze the original completely and make my own version, Return To Sender, matching every color and pattern as closely as possible. I liked the idea that I would use my own archive of envelopes for my effort and it would therefor be doomed as any kind of accurate copy. My piece would be more like a translation or a re-performance of the original.

In the process I discovered that there are blocks whose details match other blocks precisely but which aren’t placed in a symmetrical position, other blocks in symmetrical position that only have a dark (or light) half that matches, and still other blocks in a correct position that are almost but not quite perfectly matching. In the end despite my best effort to learn everything I could about Mary Jane Smith’s quilt, I am left with more of a mystery than when I began.

Hand-drawn analysis of Mary Jane Smith (1833–1869) and Mary Morrell Smith (1798-1869) Log Cabin Quilt, Barn Raising Variation

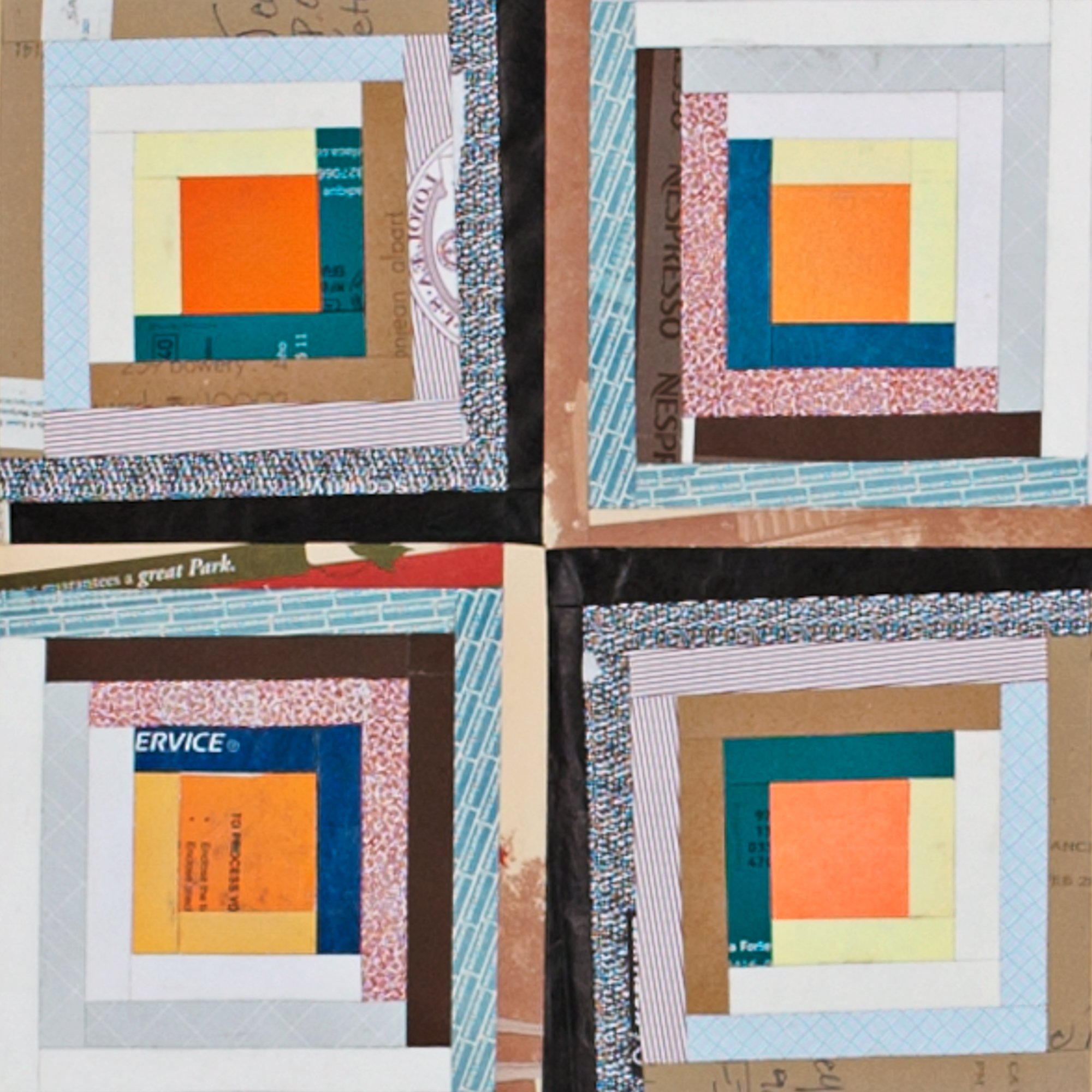

Afterthought (after Anonymous, 1880-1890), 2010

Left: Afterthought (after Anonymous, 1880-1890), 2010 Right: Eisenstat, S.L and Warren, E. V., Glorious America Quilts: The Quilt Collection Of The Museum Of American Folk Art, New York, NY, Penguin Books, 1996, pp.166

Afterthought is based on a child’s crib quilt made by an anonymous person in Maine between 1880 and 1890. The Starburst pattern is quite common in quilt making but the typical geometry could fit two equilateral triangles into each diamond shaped piece and it produces six pointed stars. Four- and eight-point stars are also common in quilt patterns. Creating a seven-pointed star is extremely unusual. I know of no other. It requires some awkward geometry and pattern cutting to achieve.

I first came to know and appreciate this quilt through a favorite catalog, Glorious American Quilts (AFAM, 1996, where the pattern is identified as Blazing Star) and when I decided to make my own version the small black-and-white photograph in the appendix was the only image I had to work with.

Leaning into the lack of color in the photograph I made the star motif with black-and-white security patterns and plain envelopes. I wanted the black-and-white star to stand out against an intensely colored background. Because Con Edison prints billing envelopes with a fascinating pattern in varying shades of blue I was also able to refer to the Japanese denim patchwork textile tradition usually called boro.

Boro Futon Cover, Artist unidentified, 1880-1910, Collection of the International Quilt Museum, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE

I never expected to have a chance to see the original quilt, given that it is usually kept in museum storage, but I assumed it would be colorful. You can only imagine my surprise and amazement years later when my work was shown at the American Folk Art Museum and the 19th-century original was hung nearby with its intense combination of mustard yellow and deep reddish brown against the turkey red ground.

Starburst Crib Quilt (artist unidentified), 1880–1890, Collection of The American Folk Art Museum, New York, New York

Correspondence (after Rachel Blair Greene, 1885-1895), 2014

Left: Correspondence (after Rachel Blair Greene, 1885-1895), 2014 Right: Rachel Blair Greene Crazy Quilt, 1885-1895, Collection of The American Folk Art Museum, New York, New York

I’ve always loved Crazy Quilts but the Rachel Blair Greene Crazy Quilt (1885-1895, AFAM Collection) stands out. It’s an allover Crazy that isn’t made of smaller blocks and has no centerpiece or other organizing principle. Crazy Quilts usually have a lot of embroidery and other decoration on their tops but in this instance I’m only interested in the piecing, the shapes fitting together. Contrary to the name, if you approach making one in any kind of crazy way it’s not going to work out well for you.

Crazy Quilt isn’t technically a pattern at all. It’s more of an instruction to be random, but within accepted limitations. I associate it with something like an overhead photograph of the surface of the ocean whose subject is itself: allover unique yet allover the same. If you have looked though other projects on this website you can probably guess that this would have an automatic appeal for me, as well as a relationship to the allover compositional strategies of much postwar American art. I wanted to echo and extend this relationship by converting the colorful embroidered and painted original into a gray monochrome. I had been looking for a way to make a gray monochrome for a while and I took the opportunity to use all thirty-two variations of black pinstriped security patterns from my archive.

In the process of making this piece I discovered that while Rachel Blair Greene’s “crazy” shapes fulfill the standard expectations of the Crazy Quilt pattern they each have a surprising amount of character. I was hoping my gray version would have fewer distractions and that it would be easier to see the character of the shapes.

Left: Hand tracing from catalogue photograph, Rachel Blair Greene Crazy Quilt, 1885-1895 Right: Shape Identification Diagram, Rachel Blair Green Crazy Quilt, 1885-1895

The catalog image was scanned, enlarged to life size, printed, hand traced, the tracing itself was scanned and reversed, and the 306 shapes were printed out separately. Shapes were then assigned to patterns and rotated to degree using a random number generator before being printed on envelope exteriors, hand cut and assembled.

I don’t dislike the result but ultimately I came to feel dissatisfied with my attempt to give Rachel Blair Greene’s shapes the setting I think they deserve. This feeling would drive me to make Forwarding I–XI and then another project and another using the same set of shapes but leaving behind the facsimile aspects of the Piecework project.

Correspondence, Pattern Distribution Table

Sender Reverse

Left: Sender Reverse, 2018 Right: Verso, Return to Sender (after Mary Jane Smith and Mary Morrell Smith, 1861-65), 2010

Sender Reverse is a further extension of the ideas behind the re-performance aspect of this body of work. Several people who have seen parts of Piecework while being moved, stored, or installed expressed an interest in how they look from the back. I like the backs, too, but wasn’t interested in showing them. When it eventually came to the back of Return To Sender I had a new idea.

Having already used Mary Jane Smith’s original quilt as a score to produce Return To Sender I wondered what would happen if I used Return as the score and performed the back side instead of the front. Some of the envelopes I had used in Return for their patterns or colors are white on their opposite sides and vice versa. As a result Sender Reverse has a different character.

Left: Verso, Return to Sender... Column 9 Rows 7-11 Center: Pattern Layout Diagram, Sender Reverse Column 9 Rows 7-11 Right: Sender Reverse, Column 9 Rows 7-11

The process foregrounds a kind of generation loss, implicit in the project as a whole but here made more visible. The bones of the original, the blacks and some of the colors, are still present but the increase in whites shows those elements mirrored in a new, almost ghostly, way. The graphic elements of Return begin to assert themselves while the Log Cabin (Barn Raising Variation) pattern that dominates the 19th-century source, as well as Return To Sender, fades and hovers in the background.

Left: Return to Sender (after Mary Jane Smith and Mary Morrell Smith, 1861-65), 2010 Right: Sender Reverse (work in progress)

Antecedents

Left: Antecedents, 2014 Right: R: Center Medallion Doll Quilt, Artist unidentified, 1820-45, Collection of Stella Rubin / Image Source: Shaw, R, American Quilts: The Democratic Art, 1780-2007, New York, NY, Sterling, 2009, pp. 43

Antecedent is based on an early Center Medallion Doll Quilt made for a doll-sized four poster bed by an unknown person between 1820 and 1845. The image on the center medallion of the original shows a three masted sailing ship.

The piece came late in the series when I had started some new work and was experimenting with inkjet printing directly on Tyvek. I incorporated that process here, printing envelope patterns as well as the image for the center medallion directly on the spun polyester material. I matched the structure and decoration of the doll quilt but, in keeping with the original, I was somewhat casual with color and pattern.

I replaced the medallion with a screenshot downloaded from the internet showing a cartoon published in the New York Evening Sun on April 1, 1913, just after the closing of the Armory Show. The cartoon, among many others, was a response to America’s introduction to cubism. Drawn by Clare Briggs, The Original Cubist shows an old woman in a rocking chair sewing a Crazy Quilt. The intention to skewer cubism at the time of the Armory Show is clear but the cartoonist seems happy to throw quilting and women’s work under the proverbial bus in the process. I was only too happy to bring it full circle.